Pathogenesis Review

on Aug 9, 2017

You are a disease, an assault on the human body. That's not an insult; it's the premise of Pathogenesis, the semi-cooperative deckbuilding game from Jamie and Loren Cunningham. As premises go, it ranks with "you are the dungeon lord" for creativity. It's only been a month since I reviewed Plague Inc., three years since Pandemic: Contagion, and the idea wasn't new even then. Slot on the word "deckbuilder," which is game publisher code for "we have a theme but no mechanics," and the tepid reception of the Cunninghams' debut release, Flying Frog wannabe Castlevania: Curses and Traitors, and Pathogenesis has a lot to prove.

Miraculously, like the tenacious little bacterium that gave rise to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Pathogenesis does distinguish itself in a big way. And it makes a big impact, primarily, by going small, snubbing the whole global epidemic scene that served as the backdrop for Plague Inc. and Pandemic in favor of a far more intimate theater of war: a single human body. Your nemeses here aren't the WHO or international quarantine efforts; they are the actual processes our bodies use to fight pathogens, invisibly, every moment of every day. As such, Pathogenesis reaches a level of scientific accuracy that makes it suitable for classroom use. Those other games were apocalyptic science fiction, but this is just science.

The educational appeal is aided by the colorful artwork from scientific illustrator somersault1824.

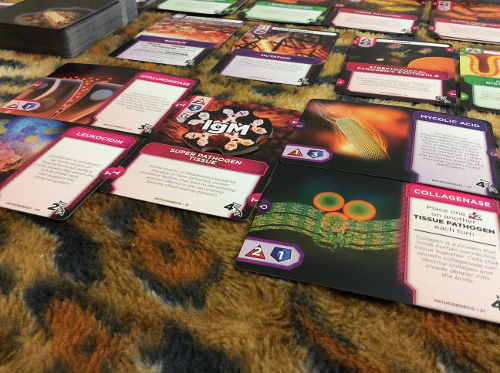

As a science game, Pathogenesis excels. The level of simulation is high enough that a description of its mechanics also serves as a crash-course in immunology. The players get points and win the game by building pathogens that cause damage to the body's systems, represented here as three tracts: respiratory, gastrointestinal, and tissue. To do so, however, they must fight through three levels of immune response. The first is passive and nonspecific: a small deck of physical and chemical barriers, like stomach acid, ciliated cells, and keratinized tissue, protecting each tract. These cards are essentially chump blockers, passively preventing damage that would otherwise be dealt to the vital organs, and gives players a few rounds to build up before the body goes on the offensive.

As soon as one of the barriers is breached, the two-stage active immune response kicks in. From that moment on, each pathogen must draw a potentially deadly immune response card before it can attack each turn. Unlike the barriers, these cards have an attack value rather than a defense, and they can wipe out your measly pathogen before it deals any real damage. Unless you increase your defense by upgrading your starter microbes into tract-specific pathogens and super pathogens, or by grafting on new traits and toxins, macrophages and other first responders can kill your pathogen outright. But the ones that don't kill you are far more insidious: fever cards dilute your deck, reducing its effectiveness, while other immune processes tag your pathogen with molecules like chemokines and C3, attracting more numerous and lethal defenders for all future turns until the pathogen is eliminated. When the initial (innate) immune response deck runs out, it's shuffled in with the second-stage (adaptive) immune response cards, which introduce even deadlier defenses in the form of Immunoglobin antibodies and T-cells. If the deck runs out a second time, the body wins (with the help of some amoxicillin), and all the players lose—that's the semi-cooperative part. If the players can first "defeat" a number of body tracts by depleting them of damage counters, then whoever dealt the most damage wins.

Traits and toxins on your pathogen's attachment points help it become a more efficient killer, while environment cards can be played for instant effects.

As a game, Pathogenesis is more of a mixed bag. Depending on which combination of cards ends up in the immune response decks, the immune system can hit with kid gloves or brass knuckles, which makes the "all players lose" condition feel arbitrary and unsatisfying; I typically just treat it like a game timer and tally up the final score anyway. Furthermore, there's a lot of ambiguity in the timing and interactions of the immune response cards, and the solo and cooperative games feel less fully realized than the core, competitive mode—particularly the solo, which is too quick and too swingy. Finally, because the immune deck is a timer, and the rate at which it progresses depends on the number of pathogens, a dominant strategy quickly arises to build one super pathogen in a single tract and invest heavily in defense, a problem exacerbated in the non-competitive modes, where there's even less incentive to play aggressively or diversify.

Pathogenesis is one of those experiences that communicates its theme so effectively that a little mechanical imbalance is easily forgiven. In fact, it's apparent in several places that the mechanics were invented to suit the theme, not vice versa; if it also results in a fun game, that's a happy accident. Or maybe there's a good reason this microscopic battle resonates so strongly: it's literally in our DNA.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist