Bruxelles 1893 Review

on Feb 8, 2017

In Brussels in the last decade of the 19th century, an artistic revolution took hold. The fin-de-siecle spirit of progress inspired artists like Victor Horta and Paul Hankar to throw off the stuffy, stagnant wisdom of the great art academies and create the first truly modern artistic style. Characterized by flowing, whiplash curves and bold contrasts, Art Nouveau is often referred to as a “total artâ€: for the two decades it remained popular, you could live in an Art Nouveau house decorated by Art Nouveau paintings and furniture, discussing Art Nouveau theater with your Art Nouveau friends while sipping Art Nouveau coffee out of Art Nouveau mugs.

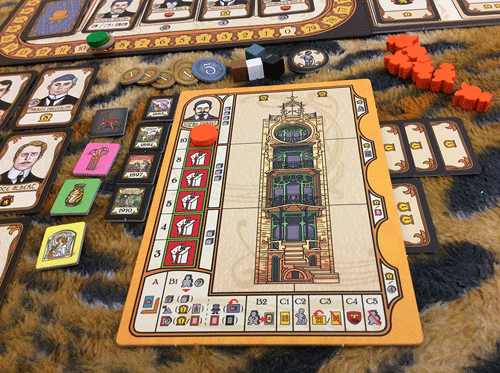

The player boards and exhibition tiles in Bruxelles 1893 showcase authentic Art Nouveau art and architecture.

Bruxelles 1893 celebrates the birth of this important art style, casting players as famous Art Nouveau architects racing to complete their masterpieces and leave their mark on the social and artistic scene. Mechanically, this is a worker placement game where every worker placed is also a bid in several simultaneous auctions. This awareness of space feels appropriate to the artistic theme and keeps interaction high without the screwage of a traditional worker placement.

Bruxelles 1893 could be called a victory point salad game, but while that term is often applied derogatorily, Bruxelles shows off the strength of this design style. It's the game equivalent of "total art." The common complaint about point salads is that, since every action grants victory points in some form or another, no move is really better than any other, and strategy suffers. Bruxelles proves this notion false. The “point salad†here is more of a sandbox: there are many reasons to place a worker in a certain spot, and just as many reasons not to. Deciding which of those to emphasize and sticking to that strategy are essential to good play: wishy-washy players will often end the game more than 100 VP short of their more decisive rivals.

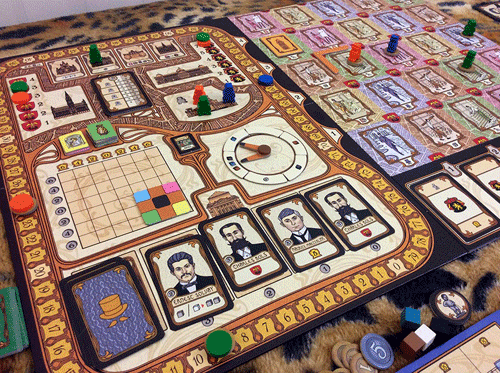

The key to this nuance is the board layout. Five strips are randomly assembled to create a new board each game. Each time a player takes an action on the Art Nouveau board, they must place an “assistant†along with a bid of at least one coin. At the end of the round, the bids on each column are tallied, and the highest bid wins the bonus card underneath that column and must decide whether to use its central power, advancing along certain point-scoring tracks or unlocking additional assistants, or to tuck the card under their player board as a point multiplier for one of four end-game scoring categories. Additionally, these bonuses might have Manneken Pis icons, and the player with the most of those becomes first player next round, with the powerful ability to define the playing space. In addition to the bids, an area majority contest for additional VPs occurs in each cluster of four spaces. All of these considerations give layers of nuance to each assistant placed before you even take into account the actions themselves. If a player can’t afford a bid, wants to take a blocked action, as a stalling tactic, or just because, they can freely utilize the four powerful Brussels spaces, but majority on this part of the board is actually negative, locking away an additional assistant.

The boards form a visually captivating puzzle that changes with each game.

The five primary actions are equally nuanced, with extra decisions accompanying each one. For example, one action lets players create a work of art, and another lets you sell them. But how soon should you sell? As the size of your collection grows, you earn additional basic income at the end of each round, and unsold art is one of the four endgame scoring categories. It’s unlikely that you’ll collect enough multipliers to beat the maximum yield of 6 VP and 6 coins, but it takes crafty maneuvering to hit that maximum each time. The more artwork you have when you decide to sell, the more you can influence the payout; on the other hand, art of the same color can’t be sold two turns in a row, so you might want to make a quick sale before your opponent can, and cash on hand is always useful in a bidding game.

Every action has this level of depth. When you take a public figure from the Royal Theater, should you treat its ability as a onetime benefit or keep the card to possibly reuse in future rounds and score at game end? Keeping the public figures is tempting but costs additional coins at the end of the game.

As the players are architects, the central action is construction, with each constructed building earning up to 15 VPs and providing additional small benefits during the game. But which space should you cover up with your building, earning a secondary action when opponents use it? Should you strive to pay the full construction cost in colored cubes, earning an additional 5 VPs, or use versatile white cubes and forego the point bonus? Will you try to place in more central locations that are likelier to be included in the playing space each round, or will you go for secondary actions that bolster your overall strategy? Visually and mechanically captivating, Bruxelles 1893 is a new form of worker placement for a more enlightened age.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist