27th Passenger: A Hunt on Rails Review

on Jul 28, 2016

Board gaming has taken several evolutionary leaps in recent years, introducing new mechanics, gameplay modes and chrome of varying quality, but the one thing that’s eluded the industry is the next evolution of multiplayer deduction game, the product that’s a step up from a party game, creates the proper tension and doesn’t require a referee or a background in matrix theory to enjoy. Now, Purple Games sends their solution to this dilemma all the way from Greece, and while it’s not perfect, 27th Passenger: A Hunt on Rails almost hits the bull’s-eye.

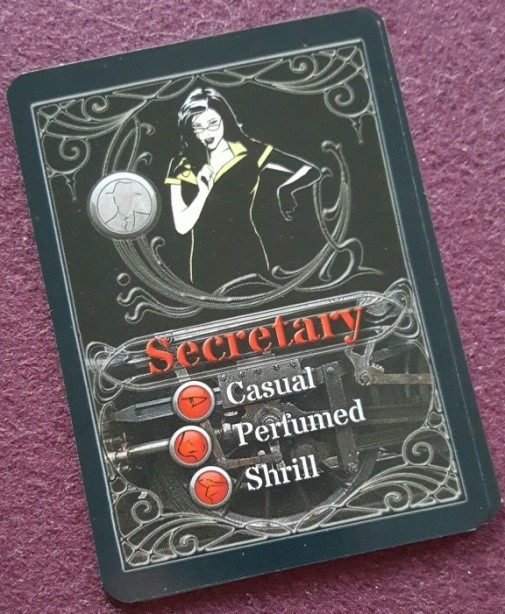

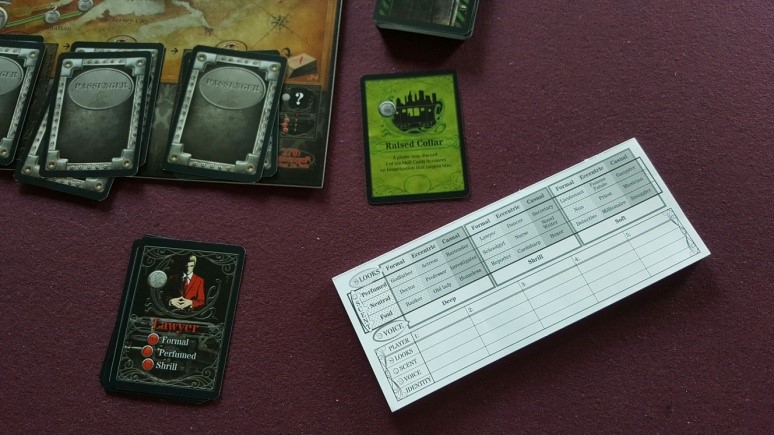

3-6 assassins board a train in 1920s New York, trying to eliminate all the other killers while avoiding innocent passengers or being killed themselves. It’s a vague premise, but it works well enough as a setup, and the game’s clever mechanics take it from there. Each player draws one of the twenty-seven passenger cards as their identity, with three unique identifying features from a 3x3x3 matrix of Looks, Scent and Voice, and must choose a single action to play at every stop on the train. In the age of expanding piles of bits and cards, the designers achieve clean success through multiplication, something the good Dr. Knizia pointed out to all of us years ago, but most of the new crop of game creators seem to have forgotten about.

Action selection is where things get tricky, forcing players to basically choose between offense and defense, and this limitation speeds the game toward its conclusion in a lot of ways. Each action has an initiative order, beginning with investigation, in which a player chooses a target, picks three of the nine possible traits (three of each type of Looks, Scent and Voice), and hands them to the target. The target compares the cards given to their own traits, hands back to the investigator any that match, and returns the rest to the pile. A swing and a miss is a mathematical possibility, but if players put a bit of thought into it, they’re guaranteed to find out at least one of the three traits with each investigation, and have a 33% chance of getting all three with one play, so lucky guesses are first game accelerator. The targeted player has a couple defenses to play, if they’ve drawn the proper Disguise card, or if they play the basic action card that prevents investigation. The downside of the latter, though, is the one-card limit, forcing players to either protect themselves or investigate others, and focusing solely on your own defense is like turtling on a world map: unless you’re playing a Euro, where nobody ever really loses, you’re going to get nailed eventually. And 27th Passenger isn’t a Euro.

After investigation cards are played comes the second accelerator: the Assassination card and it’s a true game-changer, because there’s no defense against it. If you know another player’s figured out your identity, you know you’ve basically got one turn left before you die, so the only real option is to take your best guess and try to get them first, if you’ve got a higher initiative card than they do. If not, you might as well head down to the bathroom at the end of your train car, make yourself presentable and hope they don’t aim for the face.

Initiative is a tricky thing in 27th Passenger. It determines the resolution of simultaneous actions, like everyone choosing to Investigate, but it’s randomly assigned at the start, and can only be changed if the person with higher initiative decides they want to. At first, one questions why you’d ever want to go anytime except first, but acting later can have its benefits, like investigating someone who’s spent their blocking card to stop another investigation previously in the turn, but once given up, it’s unlikely you’ll get high initiative back, so would-be assassins must weigh their options carefully; if you’re last to act and your identity’s been discovered, your game’s over.

A third action option introduces another strategic element to the game, allowing players to observe who’s recently left the train and intimidate one of the remaining passengers, quietly eliminating one to four characters from consideration, since passengers who exit the train don’t become public knowledge until three turns after they’ve left. This gives players more variety in their actions and can be a more subtle strategy for victory, but it’s at odds with, and frequently loses to, the game’s third accelerator: player count.

At the lowest end of the player range, it’s possible for everyone to know everyone else’s identity before the train’s completed half its journey, and lucky guesses or focused investigations can reveal a fellow assassin in the first couple turns, so a three-player game becomes a speed race, eliminating many of 27th Passenger’s tactical options. The tables can be turned on an investigator, blocking them and simultaneously forcing them to reveal traits, but only once per turn, and if you’re on the short end of the initiative stick, your days are numbered from the start. Longer player counts give a deeper game, forcing players to spread the love around, and that’s where 27th Passenger shines, bridging the gap between Clue and Sherlock Holmes to deliver a tight, fun deduction game.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist