Albion's Legacy (2nd Edition) Review

on Oct 26, 2016

Fated conceptions are something of a motif in Arthurian legend, the birth of a king requiring all sorts of trickery and guile, and we can find the same forces at work in the conception of Albion's Legacy, an inbred bastard of a cooperative game leaning heavily on inherited glory. That this game got a second edition, let alone a first, can only be attributed to fey glamour, the kind of ocular wool-covering that convinces you it's a good idea to sleep with your evil half-sister. Like Bush at Yale, the game relies entirely on its legacy to get in the door, and keeping it there will test even the most diehard Arthurian's devotion.

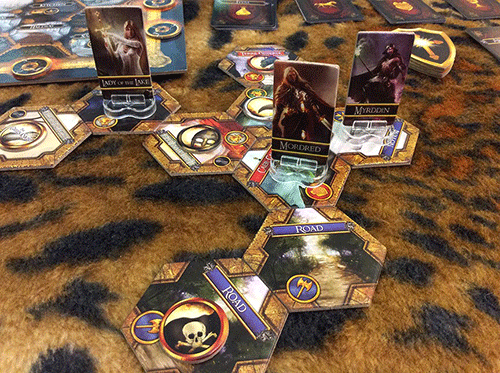

You'd think Arthur & Co. would know their way around his own kingdom.

The gameplay is a mishmash of borrowed elements (another parallel to the original myth) that worked better in their original setting. As characters from the Morte D'Arthur, players roam the lands surrounding Camelot in an attempt to complete a specific quest, three of which are included in the box. None of the truly iconic quests, notably the Holy Grail, made it into the retail edition. All of these quests involve scouting specific locations in a giant stack of realm tiles, which can be explored from up to three locations a la Betrayal at House on the Hill. Meanwhile, players will also need to collect quest coins, primarily by defeating the roaming threats that pop up when tiles are scouted: generic witches, saxons, druids, dragons, and named enemies like the Green Knight, Agravain, or Cath Palug. Combat and other challenges are attempted by rolling the "Stones of Chance" based on your character's attribute scores, in standard adventure game fashion, but most of the gameplay boils down to playing "Find the Grail in the hay-wain" with those realm tiles.

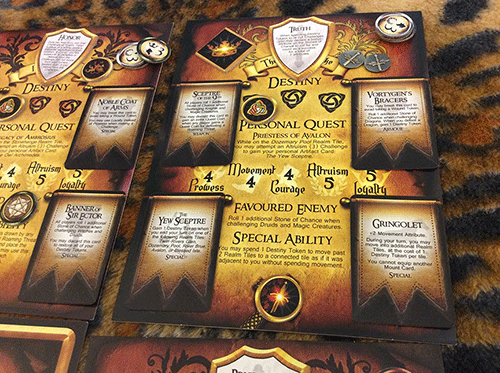

For a second edition, Albion's Legacy still suffers from a host of design and production issues. The rules layout is confusing, and the rules being described often feel arbitrary and poorly considered. For example, players receive four inventory slots: one weapon, one armor, and two specials. However, these inventory cards are drawn at random from multiple piles (items, armory, relics, mounts, et cetera), with no guarantee that the card you draw will fill the slot you're wanting to fill or be relevant to your character. Many armory cards say things like "You can use Altruism in place of Prowess," fairly useless for a character whose Prowess exceeds his Altruism. Replaced cards must be immediately discarded, removed from play. Players can trade cards, but the process is poorly conveyed in the rules, making it unclear if swaps are allowed. Scouting realm tiles is even more arbitrarily convoluted: scouting does not use up movement, but you need at least one free movement point to do it, and if you want to continue scouting, you must immediately move onto the newly scouted tile unless that tile creates a dead end, in which case you may continue to scout from your current position. That's a lot of rules and exceptions for one of the game's most common actions.

Caption: The graphic design is all form and no function.

The components design is also flawed. Realm tiles, including the "tiles" printed directly onto the Camelot board, can have icons printed on them which are split into four main groups: some give you a special action, like a card draw, if you end your turn there; others provide bonuses to challenges when occupied by a character; others force a Threat draw (universally bad, but also necessary to complete the game) when scouted; and still others force an Encounter draw (either good or bad) when moved over. Despite the differences in timing and impact of these effects, all of the icons are printed in the same gold color, and several of them look frustratingly similar, like the icons for forge and encounter (an axe versus a hammer) or healing and secret path (two balanced crosses). The iconography of the inventory cards is doubly flawed: the crucial detail of which inventory slot an item fills should have been indicated iconographically, and though most cards give the player additional bonuses when challenging specific enemy types (already depicted iconographically on the enemy tiles), these abilities are all conveyed through blocks of small text, making it necessary to reread the cards continuously to evaluate your fighting strength. Finally, the open and closed paths on the realm tiles (in the same gold coloration as the icons) is difficult to read from a distance. The compounded effect of these rules and graphical presentation faux pas is a barrage of little annoyances, not the kind of atmosphere you want in an adventure game.

The fact that the legend is universally familiar and the art is pretty was obviously enough for some people, but with Shadows Over Camelot still in circulation, there's no reason for anyone to settle for such a subpar Arthurian adventure.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist