Castles of Burgundy: The Card Game Review

on Jul 21, 2016

Castles of Burgundy was Stefan Feld's breakout hit--not his first success, but the one that reached the widest audience. From that perspective, Castles of Burgundy: The Card Game makes a lot of sense: take what made CoB popular and strip down the complexity and the components to reach an even wider audience at half the price. But in this quest for simplicity, was too much lost in translation?

If you had asked me after my first game, the answer would have been "yes." CoB: The Card Game jettisons more than just the dice and tiles of the original. It also loses about half the playtime, a lot of the tile variation, and the spatial, route-building aspect that gave Castles a lot of its staying power. In final measure, though, after the culture shock wears off, the heart of the experience remains to a surprising degree.

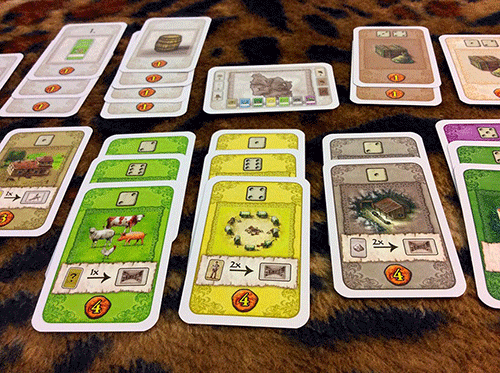

In place of its big cousin's array of player boards, tiles, and dice, CoB: The Card Game uses a thick deck of multi-function cards. When they are in your hand, they're dice—you simply ignore everything on the card except the number at the top, from 1-6. When they're on the table in front of you, they represent construction projects, analogous to the original's tiles.

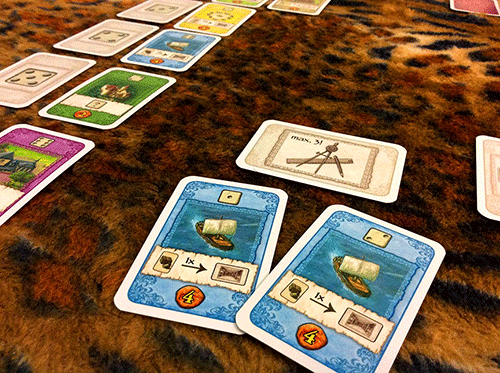

The basics of what you can do with your "dice" haven't changed much. As players build their estates in 15th-century France, they'll mostly be drafting cards from the center display by playing "dice" matching the card's row number (six "display" cards help keep track), or placing those drafted cards into their estate, this time by matching the value of the card itself. Other potential actions include taking "workers," which can be spent to alter your die's value up or down, or selling goods, gaining points and silver. Silver can be spent in a kind of black market for what amounts to a bonus action: in addition to your normal turn, you can spend 3 silver to draw 3 cards and choose one to add to your current projects or use for its die value.

Just like the original, the key to the card game's charm is that for each project you add to your estate, you immediately get a bonus action determined by that card's color. Blue ships let you take one of two visible goods; light green pastures let you take animals, trying to build sets of 4 unlike critters; yellow knowledge cards give you workers; et cetera. Of special note are the titular dark green castles, which grant you a free action; the tan buildings, which provide a wide range of effects; and the purple cloisters.

Cloisters are the card game's major addition (they made an appearance in a mini-expansion for the tile game). They have no immediate effect, but they can pose as a card of any color. This is important because the main way to score points in CoB is to complete sets of same-colored projects. In this case, rather than regions of various sizes, players just need to worry about collecting triples, at which point they score that card's value (usually 4). Completing a triple also gains you a bonus, the earlier the better: early rounds offer a much wider menu of rewards, and small achievements go to the first player to complete a triple of a given color.

Experienced Burgundy players will have noticed several of the card game's major omissions already. Most notable are the greatly simplified knowledge tiles and the abstraction of the estate's various regions. Another huge change is that the project cards come out in a totally random order, whereas the original tiles came out in a predictable way, at least by color. This alters the mood of the game in a way that suits a card game: the ability to strategize future rounds is replaced by a more push-your-luck tension.

As a dedicated Feld nut, I met most of these changes with initial resistance. So much of the nuance had been stripped away—the special powers and scoring based on yellow tiles, the strategic ramifications of differently sized regions, and the route-building element, wherein a newly placed tile must touch one already on your estate board.

As I played more, though, I found myself wondering if these elements really led to nuanced strategy or were just complicated for the sake of being complicated. While the triples don't do justice to the puzzle of completing a six-tile region of building tiles without being able to play more than one of each kind, they do create the same final-round brain-burn as you try to complete your final sets and end the game without any unbuilt projects or unsold goods sitting in your storage. And it recreates that feeling in half the time, in a portable format, with an even more teachable ruleset.

In the end, it's probably the best thing it could have been: not a replacement for the original, but a lighter, faster, and cheaper alternative that feels close enough.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist