Die Palaste von Carrara (The Palaces of Carrara) Review

on Dec 1, 2016

A while back, I watched a documentary about an Italian chef who got pissed off that everyone was eating his ravioli too quickly, so he changed the serving size to one raviolo per plate. Suddenly, he was getting rave reviews. This might tell you something about the pretentiousness of food critics, but it also illustrates an old adage: more of a good thing isn't necessarily better. I love complexes of interlocking game mechanisms and divergent paths to victory, but restraint can be just as enticing as excess, and Die Palaste von Carrara (The Palaces of Carrara) is the perfect, single-dumpling plate of Euro-gaming goodness.

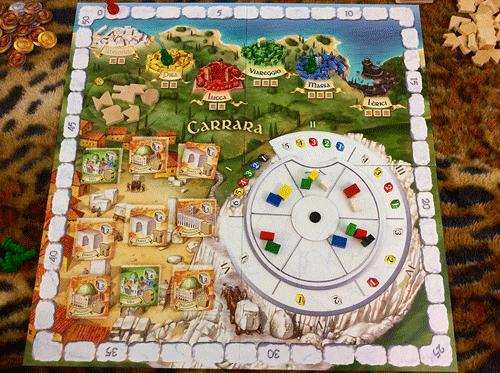

Carrara's wheel is the perfect illustration of its "less is more" mentality.

Designers Wolfgang Kramer and Michael Kiesling are household names among certain circles of board gamers thanks to their award-winning Mask trilogy (Tikal, Mexica and Java), not to mention Kramer's El Grande and the timeless 6 Nimmt!. However, Carrara is a far cry from the area majority and action selection mechanisms the duo helped to popularize. Instead of burying players' faces in a spreadsheet of 7+ distinct actions of varying costs, Carrara keeps things simple: there are three actions, and you can choose one per turn. That's it.

It's this kind of elegance that's the mark of a really good European-style board game. The best Euro-games can be played with the rulebook closed; everything players might forget should fit onto a single player aid. Carrara doesn't even need the player aid.

Of course, simplicity of rules doesn't mean simplicity of choices, and Carrara achieves impressive depth of strategy by making all its actions interdependent. As city planners in Italy, players can either buy resources, spend those resources to build buildings in various cities, or score the cities to receive coins and/or points. The resources are purchased from a spinning wheel that functions as a sort of circular conveyor belt economy. With every purchase action, the wheel rotates and new resource cubes are added to the first, most expensive sector. A cube's current place on the wheel dictates its cost: white cubes are always the most expensive, but they can cost as many as 6 coins or as few as 1, depending on their position on the wheel. Meanwhile, less expensive cubes just get cheaper and can even be "purchased" for free after enough rotations.

A cube's cost, relative though it is, also determines its usefulness. To build a building, a player must pay cubes equal to the building's cost, but the cities in which the building can be built are determined by the cheapest cube paid. You can use white cubes to build anywhere, but pay even one black cube, and you are restricted to Lerici, the butt-monkey of the Italian countryside. Meanwhile, lush Livorno requires you to pay the entire cost in white. Using more expensive resources as "wild" lets you build bigger buildings faster, but the eventual payoff won't be as great.

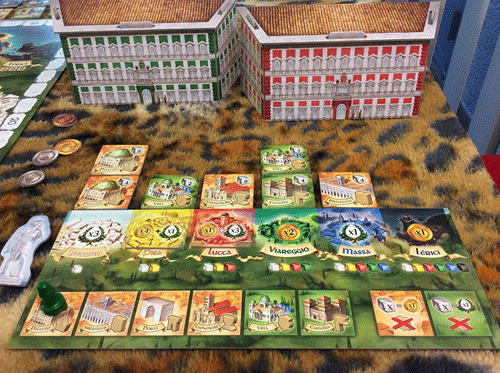

It's also a really pretty game. Look at those player screens!

Finally, the cities you choose for your building sites affect the scoring action. When you score, you either choose one type of building (there are six) or one city, and you get payout for every building of that type or in that city. The building's cost gives a base amount, but its location acts as a multiplier: Livorno pays out 3 points times the cost of its buildings, while Pisa gives coins instead; Massa and Lerici, the cheapest cities, provide 1/3 the payout. Scoring also provides wooden "objects" based on the buildings' types, which are used in endgame scoring.

The excruciating knife-twist to the design is that each building type can be scored only once per player, and each city can be scored only once per game. You want to build up your multiplier to make your once-per-game scoring actions count, but you have to weigh need and speed—scoring is the only way to get coins after the start of the game, and if you wait too long to score, you might lose your chance completely—against maximizing your jackpot. Furthermore, the entire game is a race to complete 3 objectives, so going for big, flashy sweeps week scoring isn't always smart. Being the player to declare end-of-game doesn't guarantee you the win, but it does guarantee someone else misses their chance to cash in.

This all describes the basic game. The advanced game adds several new rules, notably the ability to upgrade cities to improve their payout, but the most important change is that the game-end conditions and scoring bonuses are randomly selected each time. A new card layout can drastically affect the feel, pacing, and focus of the game, meaning there's never a surefire, one-size-fits-all strategy. The last two games I played, I got caught off guard and missed my chance to take the big scoring actions I'd been working on, but I won it all back when it came time to tally the "Extra Karten" scoring bonus.

A game doesn't always need a dozen discrete actions and five scoring tracks to have depth and complexity. Sometimes, all you need is a single, well-made raviolo.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist