Orongo Review

on Sep 8, 2016

If you were going to design a game based around the tribal warfare and sharp resource depletion which occurred on Easter Island, a blind bidding game consisting primarily of collecting sets, building routes, and placing tokens might not sound like the route that you’d take. But then again, you’re not Reiner Knizia, are you?

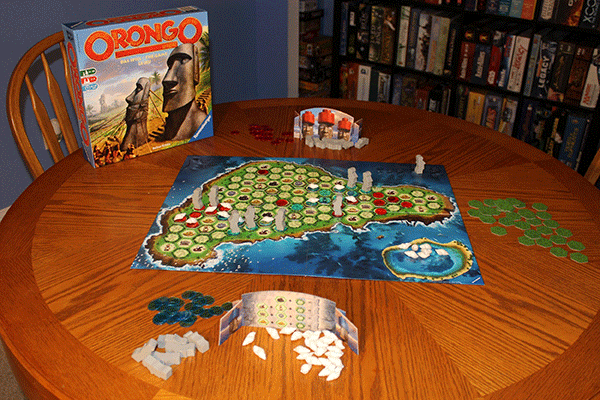

Orongo tells the tale of the settlers of Easter Island, complete with the conflict inherent with various clans staking their claim to the island’s scarce natural resources. It also features the strange, iconic moai statues that begin to pepper the island’s coasts, until one player manages to build the one moai to rule them all and win the game.

So I make light of Knizia’s typical abstract game design, but here it represents a smooth way to communicate the island’s ever-decreasing natural wealth and the struggle to hold onto and exploit as much of it as possible. As players blindly bid shells for the right to stake out certain areas of the island, the winner pays a stack of the plastic currency to a common pool, while the losers get to hang onto theirs and take a lesser prize. When players run low on shell-cash, they can bid nothing in order to claim the pool.

Therefore, it’s almost a closed economy—with one snag. Whenever you manage to connect a set of related resources and a coastal island space, your abstract islander clan strips that area dry and erects one of the imposing moai, forcing you to spend one or two of your shells permanently onto the corresponding space. What this all adds up to is an economy that’s slowly shrinking: players will throw around shells as if it’s going out of style in the first few rounds, but by the time the last, hotly contested spaces come up for auction, meager bids of “three†or “four†are not uncommon.

It’s really quite clever.

Why then isn’t this my favorite Knizia of the last decade or so, forcing the Review Corner to issue its first ever six out of five star review? First reason: the components. While the moai are gorgeous and look amazing on the board, and the shells are a fun tactile piece to mess around with, the latter roll around such that players start reminding one another not to take a breath, lest the whole game be ruined. Furthermore, the tiles that are up for auction are all but indistinguishable from the unavailable spaces beneath.

The problem is so pronounced that every last person that I either played this game with or showed it to as they walked by immediately mentioned the issue. It’s so glaring that I simply refuse to believe anyone ever playtested this game with the final components. Yes, it is that bad.

Now, there is some hope. Once you get used to the shells, you can balance them like a pro. As for the tiles, creative people have posted a workaround in the form of highlighting the cardboard hexes with a bit of permanent marker. Thanks, internet, for saving this game for me.

That’s not to say it’s a mechanically perfect design, though. The game’s narrative, while interesting and dynamic, does not vary significantly from game to game, so there’s a “been-there-done-that†feeling after a few sessions. However, Knizia fans will almost certainly begin to appreciate subtle differences as they dig deeper into Orongo’s deceptively simple design, especially in the game’s noticeable change in competition and feel from two up to four players.

I also feel that the early game is simply not as interesting as the late, much tighter rounds. Gamers may not know exactly what to bid, especially if they haven’t played before, and there are a lot more spaces to go around, making the auctions less tense. This is not atypical of Knizia’s most iconic designs, as games like Samurai and Tigris & Euphrates both feel much looser and more open in early rounds than in the cut-throat, insanely tense final moments of the game.

Still, I almost view this as a positive. The game relies heavily on players to decide how much shells are worth and what to bid by reading their opponents, rather than forcing players down a scripted path each and every game.

So while Orongo’s interesting, unique mechanisms offer a highly thematic take on the mysterious Easter Island, they’re topped by the high level of player interaction that the game offers. If you’re a Knizia fan, pick it up, no questions asked. If you’re not, you may not appreciate it as much as fanatics of the good doctor’s work, but I almost guarantee you’ll at very least admire the design, terrible production issues aside.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist