Editorial - Reiner Knizia, Master of Theme

on Mar 9, 2017

Over the past few years, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking and re-thinking about what makes a game thematic versus abstract. I reached a certain impasse, a level of dissatisfaction with games that were regarded by gamers with the dreadful “dripping with theme†appellation, which almost always means that a game has plentiful artwork, nomenclature and lore regardless of the relative interchangeability of mechanics derived from a stock list of routine processes and procedures. I’ve argued in the past that there are levels of theme occurring at “executive†(illustration and fluff) and “conceptual†(mechanics and contexts) levels. But a few games that I’ve been revisiting of late have caused me to completely rewrite the Barnes Position on theme in games- where it exists, what generates it and what it should be doing as part of a design. It may surprise many readers, who have bought into a certain online gamer forum party line, that all of these games were designed by Reiner Knizia. For as far back as I can remember- going back to rec.games.board newsgroup at least- the general consensus was that Dr. Knizia was the case study for the pasted-on theme, a layer of pictures and text to impart a post facto sense of meaning or setting to colored, numbered cards or auctions.

The Great Man himself, Dr. Reiner Knizia.

Truthfully, if your understanding of theme in games is a direct function of how many plastic miniatures are in the box, how much flavor text there is on the cards, the quality of the drawings in the rule book or how much dice-rolling there is in it then certainly a Knizia design isn’t going to be regarded as “dripping with themeâ€. But if by theme you want and expect a game to provide a formalized, abstract explication of more literary and interpretative contexts and meaning then some of Knizia’s best games reveal him to be a far greater master of expressing theme in games than any of Fantasy Flight Games’ house designers.

Modern Art (currently out of print), which I recently reviewed as part of my Eurogames Reclamation Project is a perfect example. It’s widely considered an “abstract†design, consisting primarily of a deck of cards depicting the purposefully terrible works of fictional artists and some money chips. Yet what the game describes is a perfect example of how rich a game’s theme- as opposed to its setting- can be. Players represent art dealers effectively trying to turn worthless art into valuable commodities. The action of the game creates these values, and players are constantly engaged in hyping up junk and paying attention to what’s hot and what’s not from season to season. The actions, as well as the themes they illustrate, serve to parody speculation and the fine art marketplace. This is all getting at a deeper function of game design than shooting zombies with a +1 shotgun or whatever.

Tigris & Euphrates is another game widely decried as having a “pasted on†theme, but when I play this Sackson-influenced tile-laying masterpiece, the theme of civilizations rising and then coming into conflict with others over resources or political, spiritual, and geographical issues blazes through the simple process. The internal conflict mechanic, for example, describes how a new leader may stage a coup within a population with the support of local religious or ideological figures. In game terms, this may just mean playing a wooden token and then some tiles. But that abstraction (and let’s not forget that all games are abstract) bears real meaning beyond the description of action. What is lost in the depiction of conflict in Tigris and Euphrates is the kind of detail that you might find in Civilization or Clash of Cultures but in return players experience a very lean, focused sense of what actions mean at their most essential level.

The story of civilization, told on a grid.

You see these kinds of things throughout the Knizia catalog, usually bound in authorial, recurring themes and mechanics. Risk-taking, balancing advantages with helping others, accepting negative values to attain positive ones and choosing your conflict from among several are concepts you see time and time again. It’s true that some of his designs skew more toward pure abstraction and away from bearing purposeful theme, but even in games like Through the Desert (another out of print title) meaning emerges. A caravan needs water. But you have five caravans, and you have to decide which to increase in value by getting them to water, which also increases their size as you add camels. It’s not Tales of the Arabian Nights in terms of storytelling, but there is a narrative there and a theme of desert survival and water as a source of prosperity clearly becomes evident.

This isn’t to say that some of Knizia’s games aren’t purely mechanical. Loco, Flinke Plinke, Thor, Quandary or whatever name you know his simple “play a card, take a chip†game by has no theme other than competition. It isn’t abstracting anything, it is raw mechanics. Many of his more recent designs- Fits, Indigo, Callisto Qin and so forth are also moving more toward exploring or iterating on mechanics without themes. An ever-growing number of Knizia designs are simpler card games that have been appointed with new “themes†such as the recent Fantasy Flight addition of Game of Thrones stills, terms and fonts to a Knizia game that used to have something to do with penguins. And there’s the case of Municipium, a compact area control game which started out with a pulp adventure setting and wound up on the market saddled with woefully generic Roman livery and horrible Mike Doyle artwork to appease the Eurogaming set. It strikes me that this whole notion of him “pasting on themes†has more to do with publishers repurposing his less specific designs with market-appeasing pictures and less with the kinds of theme he builds into his more significant work

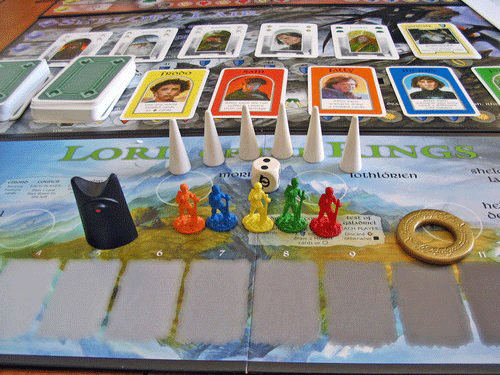

Knizia is a tremendously versatile designer and despite his name appearing on hordes of games with genuinely pasted-on settings (Cthulhu, zombies, donuts and so forth), he has done games that are closer to what most gamers would regard as “thematicâ€. His 2000 masterpiece, Lord of the Rings, is one of the most thematic games ever published not because it literally recounts Tolkien’s entire story as an abstraction, but because it describes the literary themes that were important to the writer. The Lord of the Rings is not “about†fighting orcs, a magic ring or even Hobbits. It’s about themes such as self-sacrifice, overcoming impossible odds, finding the strength to endure corruption, friendship and other very human, very universal concepts that reach much further than the fantasy nomenclature and settings.

Knizia’s Lord of the Rings does exactly the same thing, regardless of how many gamers whine and sniffle at the fact that the primary, highly abstracted procedure of the game is playing cards representing four different heroic values to move a token forward on a track. For these gamers, War of the Ring is likely a much better representation of the setting although what it describes is action much more so than theme. Knizia’s concept was to convey both the literal and literary content of Tolkien’s work, and when you are faced with a do-or-die situation in the game where you have a choice to risk putting on the Ring and falling into corruption to save the party, it’s clear that this game is pasted on to its theme- not the other way around.

A stunning masterpiece of thematic game design and one of the best games ever created.

Five years later, Knizia would do something almost as compelling in terms of expressing theme with Beowulf (yep, out of print), a game that even I didn’t really quite get when it first came out. Back in 2005, I wanted a Beowulf game where you could “be†Beowulf, fighting Grendel and accomplishing heroic acts from the celebrated epic. But this was a game where you played sets of “friendship†cards to win auctions. Honestly, at that stage in my gaming life it could have been a Talisman clone in Beowulf drag and I would have been happy. But revisiting the game here in 2014, I’ve been nothing less than shocked to find how richly thematic it is.

Knizia’s take on Beowulf is highly interpretative. That means, do not go into this game thinking that “Beowulf†is a theme. In this woefully underappreciated FFG release, players represent members of Beowulf’s retinue. The idea is that you are trying to effectively keep up with- and impress- this archetypical superhero figure by rising to various challenges. But in Knizia fashion, you just don’t have the strength or endurance (represented by your cards) to do it all. So the theme that emerges is one where players are made aware of the traditional heroic narrative and participate in all of the risks, triumphs and defeats, but at a distance from Beowulf. He is going to make it to the end and be the hero, regardless of what the players do or how badly they fail. Because Knizia wants you to know that you aren’t as good as Beowulf. Who could be? The best you can do is to try to be as good as Wiglaf, and to do that you have to play cards that abstract the core actions and values at the heart of the epic, strategically conserving and exerting strength. The game doesn’t need flavor text, excessive detail or elaborate mechanics to drive its narrative toward its thematic goal of having the player experience heroic fantasy as participator, an observer and most importantly an aspirant.

The evidence for Knizia’s economic mastery of theme goes on and on, often in subtler detail than is usually expected in so-called “thematic†games. There are the Nile tiles in Ra that have to be flooded for them to have value. The persistence of the Pyramids- the only relics of the first half of the game that remain standing- in Amun-Re, newly reprinted as of this posting. There’s the desperate struggle to keep Frodo hidden in his two-player Lord of the Rings: The Confrontation. High Society is as much about saving money and being prepared for disaster as it is the excessive spending of the wealthy. Consider the simple, hugely thematic concept of choosing which expeditions to risk investing in over the course of a game of Lost Cities. And then there are any number of “play or pass†mechanics that Knizia uses in everything from Taj Mahal to Blue Moon that represent players, leaders or factions resting, strategically withdrawing to marshal strength for the next fight. That’s a theme in itself, and one that is deeper than what is usually seen in games “dripping with themeâ€- which too often means that the design is built on top of relatively generic mechanics and laden with pasted-on pictures, nomenclature and fluff text.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist