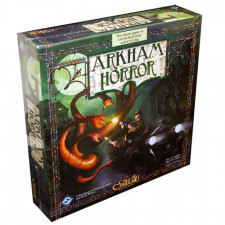

Arkham Horror Review

on Oct 29, 2015

Kyle:

KM: Perhaps no modern game carries with it as much fame and notoriety in equal measure as Fantasy Flight’s revision of Arkham Horror. It’s well-known for its rich horror background, lovingly transposed from both Lovecraft’s novels and Chaosium’s storied RPG setting. It’s also somewhat notorious for a complex ruleset, full of exceptions, details, and granularity. Bizarrely, Arkham’s fans seem to love both the narrative and the number crunching that drives the story forward.

BC: I think you hit the Mi-Go on the head (pardon the awful Lovecraft pun...there are probably more coming). For me, a large part of Arkham Horror's allure comes from the sheer inhuman massiveness of it, especially once you start adding in expansions. (In fact, I'd argue that you're not really playing Arkham Horror if you aren't using at least one expansion.) There's something very satisfying about looking at over a dozen towering decks of cards, a too-large-for-its-own-good board, and mountains of chits and tokens and know that you are going to experience, at best, only about 5% of that content in any given game. It also fits nicely with the Lovecraft theme, which emphasizes man's insignificance in a vast and unknowable universe. (Lovecraft was simultaneously fascinated and terrified by the latest scientific advancements of his day, which influenced some of his most famous stories.) But I can also understand that, to its detractors, the game is simply unruly and overcomplicated, with not enough strategic payoff to balance the burden of keeping all its little plates spinning. Am I getting that about right?

KM: I think so, and I land firmly in the detractors’ camp. But it’s not just about strategic payoff, since I think most Lovecraft enthusiasts come for the story rather than to fiddle about with any Euro-style min-maxing. The problem with the 2005 monstrosity is that both the game’s original 1987 form and its spiritual successor, Eldritch Horror, offer narratives that are at least as deep as this abomination without the annoying rule minutia. Any game’s rule set should be built to carry the rest of the design, but with this version, they end up overshadowing the doom-laced tales of horror that the group should be focusing on. It’s not endearing; it’s a sign of bad game design.

BC: Well, that sort of takes the thunder out of my next point. For me, the game’s flaws (which I’ll be the first to point out) are a charm point. They give it character; I’d rather listen to Tom Waits grind his way through a muffled circus melody than some perfectly mixed pop single. That might sound odd, but I think the fact that Arkham Horror tries to do so much (and sometimes stumbles) is directly tied to its fan community’s almost total embrace of variants and house rules. Between that and 6 years of modular expansion content, no two game groups play Arkham Horror in exactly the same way. That gives you a sense of ownership over the game that the more streamlined versions don’t deliver. It’s more like Cosmic Encounter or Twilight Imperium in that it’s less of a game and more of an activity, a gathering, maybe even a cultish exaltation that goes way beyond the game’s mechanics or whether you win or lose.

Not that I’m Arkham’s most devoted fan, but I can definitely see why there are people who refuse to make the switch.

KM: I do understand the appeal, as the game’s construct really is sound. A crescendo of doom that rises throughout the play, players who should be getting stronger with better equipment as the game goes on--these things do make for a compelling narrative. If Arkham were the only game out there with these elements, I’d probably be forced to play it and find a way to make it work. As it is however, we’re looking at a game that isn’t designed as well as most cooperative games before or after it, no matter what it has going for it in terms of setting and mood. The mechanisms themselves just don’t provide any additional payoff when you compare them with the game’s predecessors and descendants. This includes the messy combat resolution, the tangled web of phases and sub-phases, and the laughably convoluted rules for monster movement.

BC: Well, at least it makes an impression. Continuing in the role of Cthulhu’s Advocate, I think you’re severely underrating the mechanics, both from the perspective of originality and functionality. First of all, when Arkham Horror (2005) came out, co-op hadn’t yet made the resurgence it has now. There was Knizia’s Lord of the Rings in 2000, Shadows over Camelot (also in 2005), and...that’s pretty much it for the early aughties. I’d suggest that Arkham Horror played as big a role in the comeback of cooperative games as Pandemic did.

KM: Fair enough. I’m not denying its lasting legacy. But the exact same construct was used in its original 1987 incarnation, and even during that dark age of game design, it managed to deliver an exciting Lovecraftian tale without burdening players with an overwrought rule set. The first iteration had much the same story arc: players running around town gathering items and elder signs, stumbling into gates to other dimensions, sneaking by monsters, and hopefully closing enough gates that reality is kept in one piece. So I just don’t think the 2005 one is as original as you seem to, as it just took the fine mechanisms of the first game and complicated them with more card decks and pointless extra steps. Finally, now that we have hundreds of options in the cooperative category, I think the last nail has been driven into Arkham Horror’s coffin.

BC: But Arkham fans aren’t just clinging to a dusty mummy; the game has some life in it yet. For any readers who’ve never had the pleasure, the game puts players in the role of arcane investigators who have to close and seal otherdimensional gates that are opening all over the fictional town of Arkham, Massachussetts. That “tangled web of phases and sub-phases†you describe is essential to how this works. In the Mythos Phase, a new gate opens up at one of the locations on the board, like the diner or the masonic lodge. At the same time, new unspeakable monsters spill out, existing monsters shuffle around on the streets, and a clue pops up at a different location. These clues are just abstract green tokens, but they represent vital knowledge about whatever it is that’s trying to rend the veils of reality.

KM: But is it all really essential? At the heart of it, there’s a good system. But countless other designs have proven you can take the same basic idea and get just about the same effect without the stacks of effects, extraneous steps, and exceptions upon exceptions.

BC: After Mythos, there’s a quick Upkeep phase where once-per-turn abilities are unexhausted and some ongoing conditions might be removed, then the investigators all move to a new location. If you encounter a monster in the streets, you have to stop and fight it unless you can pass a sneak check, and that ends your movement, but otherwise, you usually end up at a location with a clue or one with a gate. If there’s no gate, you have an Encounter at that location, drawn from a deck of Encounter Cards specific to that neighborhood, and you also gather up all the clues there. If there is a gate, you get drawn through it and have to spend 2 turns in another dimension, where you will have a more dangerous and unpredictable Other World Encounter. Once you’ve done your time, the gate spits you back out where you started, and you get a chance to try to close it (by succeeding at a die roll) and spend 5 clues to seal it, with sealing 6 gates on the board being the main way you can win. That’s missing a ton of details, but it’s the gameplay in a nutshell.

The thing is, though, that these rules are greater than the sum of their parts. They appear messy and convoluted on the surface because, well, because they are, but also because they’re a little bit opaque about what they’re trying to accomplish. These aren’t just rules for how to play; the AI of the game (not just the monsters, but the game itself) is programmed into every rules phase. It allows for those classic moments where the game seems to have a mind of its own.

KM: Granted, when a design has so many pointless widgets and gears sticking out all over the place, on occasion, it’s going to spit out unique plots that you just don’t get with a more streamlined set of rules. What is it they say about broken clocks? But the heart of my complaint is that the one time in a dozen that something really cool happens by accident isn’t worth the long play time. It isn’t worth the tome of rules, the printed-out cheat sheets, FAQs, errata, and house rules. You get almost no payoff for all of that.

I just don’t buy that the rules have this secret effect of doing so much more than they appear to do on paper. I think it’s a situation where it’s inevitable that neat, Lovecraftian moments are simply going to happen when you stuff a pile of flavorful card with great, moody art in a box, stick a mangled set of rules in there, and let players have some fun with it. We’ve enjoyed some terrible game designs, where just the right card got pulled at just the right moment, and we all had a good laugh--but we were under no illusion that the game was a masterpiece. I think the game is seriously flawed, and if it is a great time for some people, it’s mostly by accident.

BC: I will concede your point...mostly. You're right that it is a broken clock. A clock with weird elliptical gears meeting at non-Euclidian angles. And it's true, a broken clock is only "right" twice a day...but even when it's wrong, it's more interesting to watch than a tidy timekeeper. Just the concept of these overlapping, ritualistic, unknowable rule sets spitting out eerily appropriate story moments fits the Lovecraftian theme. It creates a game that's semi-unpredictable: it follows certain constant rules (e.g. crescent moon monsters move more often than octogon monsters), but there is enough randomness that it might choose behave in the exact opposite way. In Pandemic, the tension is consistently tight because you know the cities that were infected most recently will be on the top of the deck after you reshuffle.

Now imagine a game where that is true most of the time, but sometimes a totally random city sneaks in there or you can sometimes draw the same city twice in a row. It all depends on what you are looking for in a cooperative game. Do you want a tight, consistent challenge? Then you should never, ever consider playing Arkham Horror. But if you want to see what uninhibited experimentation looks like in a board game, pick up Arkham and at LEAST two of the big expansions (I am not kidding when I say they are essential to the experience...without them, the game is TOO well balanced, TOO refined). It's like those Skyrim glitches where the enemies suddenly start breakdancing and then spin off into the air like a helicopter: you have to be patient and grind kill a lot of mudcrabs, but when they do happen, those moments are priceless.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist